In early 2019, following surgery and a few months of hospitalization, my grandmother checked into a nursing home. Due to complications after the surgery, she was bed ridden and had trouble communicating. My grandfather, having gone through his own cycle of nursing home rehabilitation a year prior, was by her side every minute of the day advocating for her. For four months, my grandmother was moved between different nursing homes. Every nursing home we went to presented us with another problem to tackle. Most of the time, it seemed to my grandfather that the nurses were not providing my grandmother with the care that he felt she required. Knowing what we know about nursing home operations, who could blame them? Each nursing home had the same, Medicaid prescribed layout: long hallways, large communal spaces, fluorescent lighting, and a high resident population. It is no surprise that the nurses could not give my grandmother proper attention when they were always spread so thin. With COVID-19 sweeping through our nursing homes, it is impossible to stop thinking about the horrors these facilities must be facing. Each resident with the virus requires such a high level of attention from these nurses that having outbreaks of infections can devastate an already under-resourced, overpopulated home. Nursing home deaths are preventable. We must redesign our nursing homes to center them around holistic wellbeing. COVID-19 has presented us with an opportunity to create much needed change in a historically unchanging field. It is our responsibility to take this opportunity. It is time we took care of those who have spent their whole lives taking care of us.

As COVID-19 continues to sweep through our nation at unprecedented rates, infection hotspots have helped data mappers identify the points from which the virus has spread to surrounding areas. Data visualization done by groups such as The New York Times and Johns Hopkins University illustrates the concentrations of infection cases around specific cities and their surrounding metro areas. Typically, hotspots have emerged as the result of a vulnerable population rapidly transmitting the disease between themselves and others around them. In the case of COVID-19, it seems that one of the most impacted vulnerable groups is the elderly population – specifically those residing in nursing homes. According to the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, approximately “40% of deaths from COVID-19 [in the US] have taken place in nursing homes or long-term care facilities.” Another report by the Kaiser Family Foundation showed that, in Rhode Island, over 75% of COVID deaths were in nursing homes or assisted care facilities. In fact, one of the first hotspots seen in our wrestle with COVID-19 was centered around a nursing home in Washington. These occurrences are merely a symptom of the United States’ broken long-term care system.

Fixing our long-term care (LTC) system goes beyond the current pandemic: nursing homes and other LTC facilities have historically been underfunded. Not providing the elderly populace with adequate care is a grave injustice, for they have earned a certain quality of life through their contributions to society and their care for younger generations. Additionally, neglecting LTC facilities proves to be a paradoxical form of ignorance: one in which ignoring the needs of today’s elderly also ignores what will become our needs down the line. Today, the “baby boomer” generation faces its own host of economic and health problems that will compound as time goes on:

Currently, ~10 million US citizens over the age of 65 are still working and 80% of this same age group has at least one chronic medical condition according to the National Council on Aging

It is estimated that 48% of households aged over 55 have no retirement savings

According to the US Census, our elderly population will increase to approximately 88 million citizens in 2050

Since more Americans will age without a comfortable savings, they will be forced to look outside of professional in-home care to treat their chronic conditions: they will be forced into nursing homes or the homes of their children. If nursing homes are crippled under the weight of the elderly population, more and more seniors will move in with their children. Though this brings many short-term benefits, long-term care in the homes of their children can bring many financial burdens. This self-perpetuating cycle has already begun. Much of the “baby boomer” generation is at retirement age and their children are having families of their own. This will hinder their ability to accumulate savings and push the burden of their long-term care onto the following generation. The cycle must be broken, and the change must begin with nursing homes that can provide the level of care that residents and their families deserve.

The problem plaguing today’s nursing homes is a flawed philosophy concerning elderly wellbeing. One way this problem can be understood is through the lens of design and the legal codes that influence it. Much like any other project, the process of designing nursing homes involves the wrestling between the client’s needs and the user’s (resident’s) needs. The clients that fund nursing homes are incentivized to adhere to state regulations regarding nursing home design in order to qualify for financial reimbursement through Medicaid. In Benyamin Schwarz’s Nursing Home Design: A Misguided Architectural Model, he outlines the bureaucratic deadlocks that architects run into when trying to design hospitable spaces for elderly residents. For example, Medicaid regulations set a minimum standard of living such that residents are not put into abusive situations. Codes set requirements such as ~80 sq ft per person in a room and place limits on the furthest distance allowed between the nursing station and the last room in a corridor. Square footage requirements, though setting a minimum area for each resident, unintentionally create a maximum possible square footage for each room. For example, a double semi-private room must be at least 160 sq ft large (due to the 80 sq ft minimum) but will not exceed 239 sq ft in practice. This is because a 240 sq ft room could, as per the regulations, fit three residents (Figure 1). Since nursing homes will want to maximize the efficiency of their floor plans, they have no incentive to give two residents the extra 80 sq ft of space when they can simply add another paying resident into the room. The latter code, concerning nursing stations, explains the monotony seen in nursing home floor plans across the country. Rectilinear forms in floor plans allow the architect to minimize the distance to nursing stations while maximizing the number of rooms along a corridor (Figure 2). These schemes are not unlike the double-loaded corridor plans seen in apartment buildings across the country. Much like nursing homes, double-loaded corridor buildings flank interior corridors on both sides with units. This allows for the greatest net-to-gross ratio, a measure of livable space to total space in a building.

The beginnings of this problem took place in the mid-20th century. The 1946 Hill-Burton Act financed the construction of hospitals for states to achieve 4.5 beds per 1000 people. This act was then expanded in 1954 to include nursing homes, putting nursing home requirements under the same umbrella as those of hospitals. In effect, this act institutionalized the philosophy under which nursing homes were financed, designed, and operated. The consequence of this institutionalization was the societal shift in perspective on elderly care. Rather than old age being seen an honorable stage of life, it was transformed into a disease to be cured. Since elderly care is meant to go on until life’s end, treating it as a changeable condition does nothing for the residents in need of care. A reversal of this new philosophy will involve a total shakeup of what we think of when we picture long-term care. It will involve an ideological deinstitutionalization of the nursing home.

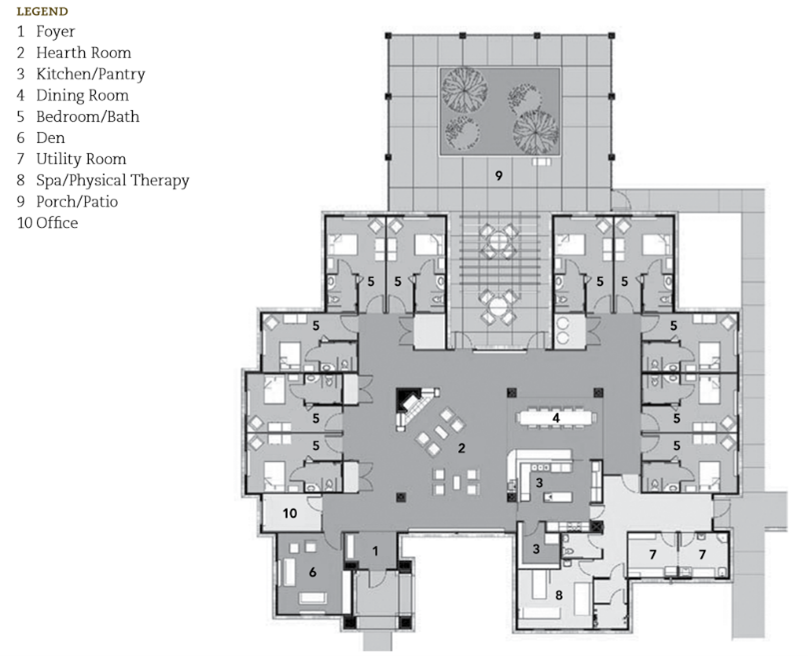

Luckily, this does not involve a leap into uncharted territory. In 2003, Bill Thomas, a geriatrician, founded the Green House Project. A “Green House” is an elderly care home that houses 10-12 residents. The core philosophy of the Green House provides a long-term care model that is not so different from life in a traditional family home. This philosophy operates in stark contrast to typical nursing homes. Rather than sterile, orthogonal layouts, Green Houses employ a plan that focuses on patient privacy in conjunction with communal, social spaces. Rooms are typically laid out along the periphery of the home, close to communal spaces such as the living and dining rooms as shown in the figure. Shared access to these spaces encourages a flexible schedule in which dining/leisure times are at the patient’s discretion. Furthermore, connection to the outdoors is also emphasized: the house typically has two access points to the outside along with an all-weather porch and sitting area (Figure 3). These elements accomplish an important goal: they improve patient happiness by flooding the house with natural light and encourage residents to interact with the outside community – a luxury seldom seen in the traditional nursing home.

Furthermore, the design elements incorporated into the house facilitate its operation as a residential home. The most important non-resident member of the house is the Shahbazim. Shahbazim are nursing assistants with 120 hours of more training than traditional nursing home nurses. They take on a wider, more personal range of responsibilities such as cooking, cleaning, laundry, shopping, and personal care. Small, autonomous teams of shahbazim take care of each house – operating out of the study room that doubles as a nursing station. As a team, they set their own schedules and roles within the house. Each team is supervised by an administrator known as a guide – though they are typically a little further removed from the day-to-day operations of the home. Since the shahbazim have more specialized roles, they are paid more (10% more than CNAs from a typical skilled nursing facility) and can develop personal relationships of mutual respect with each of the residents in the Green House. This results in higher job satisfaction and higher retention rates as compared to nursing homes. Traditional nursing homes, being historically understaffed, run into issues of neglect not seen in Green Houses. In Germany, a third of long-term care employees leave their jobs after one year. Additionally, according to the OECD, nursing home workers are paid 35% less, on average, than those who do similar jobs at hospitals. The efficient, meaningful operations of the shahbazim are facilitated by the designs of the Green Houses. Private rooms allow the shahbazim to give individualized care to each patient while communal spaces allow them to coordinate the activities of the overall home. Because of the more intimate and personalized design of the Green House, there is a much lower chance that the traditional problems of the nursing home will manifest. The smaller, group-based setting facilitates a holistic approach to wellbeing where the residents feel at home and the shahbazim can provide personalized care to each resident (Figures 4, 5, and 6).

Green Houses fulfill the same Medicaid requirements as traditional nursing homes. A clinical support team, typically found in a nursing home, visits the house on a scheduled basis and functions as a group of private guests. This guest-resident dynamic is indicated in various moments throughout the house’s design. For example, the front of the home uses a foyer to serve as a transition between the entrance and a communal space. This means that upon entry, the clinical support team is not immediately subject to the private areas of each resident and is instead transitioned from the outside into the unique atmosphere of each home. The clinical support team is comprised of medical experts that can provide more specialized care to the residents. Though the usage of a lower-resident home may seem like a cost-adverse strategy, an observational study done by the Green House Project showed that over a 12-month span, the difference in total Medicare and Medicaid costs per resident ranged from $1,300 to $2,300 less for Green House residents. The likely causes for this result are the inefficiencies arising from the overall approach to care in traditional nursing homes: nursing homes typically see significant rates of depression which can stymie improvement to a resident’s condition. Furthermore, Green Houses see a 7% decrease in the rate of hospitalization (The Atlantic, 2015). Another important efficiency of the Green House is in the versatility of where it can be located. Since the homes are decentralized and no different from a typical home, they can be easily integrated into everyday neighborhoods (Figure 7). This has enormous benefits for both residents and the overall community. For residents, being part of a larger community enhances the feeling of the Green House being a typical residential home. For the community, especially in times of a pandemic, small elderly care homes can significantly reduce the likelihood of an infectious hotspot. As of May 2020, just 8 of the 243 American Green Homes saw COVID-19 infections.

Figure 1: “Spatial Constraints” Source: Malav Mehta

Figure 2: A typical nursing home floor plan. Source: NURSING HOME DESIGN: A MISGUIDED ARCHITECTURAL MODEL - Benyamin Schwarz

Figure 3: Floor plan of a Green House in Youngtown, Arizona. Source: The Green House Project

Figure 4: Interior of a Green House at Clark-Lindsey Village (Urbana, IL). Source: The Green House Project

Figure 5: Interior of a Green House at Mirasol (Loveland, CO). Source: Green House Homes at Mirasol

Figure 6: Interior of a Green House at Saint Elizabeth (East Greenwich, RI). Source: Saint Elizabeth Community