Public infrastructure projects can have marked impacts on real-estate values. The externalities, or side effects, of infrastructure projects have the power to transform the area in which these projects take place. When projects are proposed, the market anticipates these externalities, whether they be positive or negative, and housing prices will adjust accordingly.[1] This is especially true when the members of the affected community have a say in what the project will provide to the area. Community contribution to projects ensures that the results will be satisfactory to most. Such was the case in what is now Boston’s Southwest Corridor Park. The park is a five mile stretch of land that is located adjacent to the right of way of the MBTA’s Orange Line, a rapid transit line. Together, these two pieces of infrastructure replaced what was originally planned to be a twelve-lane elevated highway connecting Interstate 95 (I-95) to downtown Boston. This transformation of the Southwest Corridor into both green and transit infrastructure made the surrounding area desirable for real-estate developers. Despite the victory in defeating the highway project and establishing needed amenities for the community, the Southwest Corridor eventually resulted in the forcing out of many residents in the adjacent neighborhoods. Both the park and the underground Orange Line led to uncontrolled gentrification in the area, causing housing prices to rise and forcing longtime residents out of their homes.

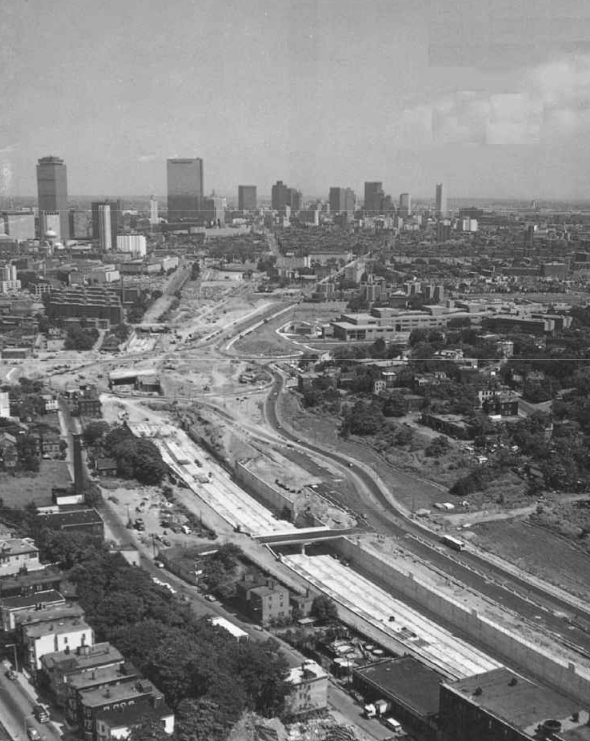

Plans for an elevated highway began in 1948 with William F. Callahan, the then director of Massachusetts Public Works. This proposed roadway would connect downtown Boston with I-95 at its intersection with Massachusetts Route 128. The twelve-lane roadway would soar above the streets of Boston, carrying with it the elevated MBTA Orange Line and all of its stops southwest of Tufts Medical Center. Additionally, this highway would connect with two other proposed roadways: the “Inner Belt”, an eight-lane ring road running from Charlestown to Brookline, and the “Central Artery”, another elevated highway that cut off the North End and Waterfront from Downtown (Figure 1). Together, these three roadway projects were to make use of funds provided by the 1956 Defense Interstate Highway Act.[2] This act defined highway construction during this time period as the federal government would reimburse states for 90% of the cost of construction. As early as 1966, structures in the way of the proposal began to be cleared. Residences and businesses of the surrounding communities were destroyed. The primarily affected communities were the neighborhoods of Egleston Square, Jamaica Plain, Roxbury, and the South End.[3] At the time, these neighborhoods were inhabited by people of many races, though their percentages of African American residents were above Boston’s average at the time. For example, from 1950 to 1980, the African American share of Roxbury’s population increased from 25% to 78.9%, well above Boston’s average of 22%.[4] Furthermore, advocacy groups were assembled to help inform communities and help them rally against the proposals. One such group was the “Urban Planning Aid” (UPA), formed by planners at Harvard and MIT. In October of 1966, the UPA released a report stating that all the families that would be impacted by the proposal would be either poor or working class, with half having incomes of less than $4,800 a year. For the Inner Belt alone, businesses employing up 4,000 total workers would be destroyed or relocated.[5] As the plans of this project were made public, the affected populations became outraged at the destruction that would come upon their communities. Aside from the physical damage of building destruction, the noise, air pollution, and other negative associations of the highway would result in environmental damage to the surrounding areas as well as health issues like respiratory illnesses.[6] As a result, massive community protests were organized against the highway plan. Thousands began to rally throughout the city, with elected officials and neighborhood leaders lending their voices to the cause. A project as large as the highway proposal warranted this type of reaction. The negative externalities that would come with the highway would make the surrounding neighborhoods unsuitable. A resulting lack of investment, in tandem with the polluting effects of the highway, would deteriorate the conditions of structures in the area. This sequence would depreciate property values in the area, stifling the already poor and working-class citizens from gaining the equity in their homes necessary to move up the socioeconomic ladder. The cyclical nature of these events would prevent future generations of this predominantly African American area from achieving better economic footing than their parents. Outcry from the community worked: in February of 1970, Governor Francis Sargent halted construction on the Southwest Expressway and the Inner Belt. He also created a moratorium on all highway construction in Boston. Three years later, the “Boston Provision” in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973 would provide federal funds for mass-transit projects.[7]

The power of community in preventing this disastrous project from being constructed cannot be overstated. After the fight against the highway, the community would have to come together again to decide what should be done to the vacant, 120-acre lot that the highway was to occupy. The master planners of this project were Donald Stull and David Lee, founders of Stull & Lee Incorporated and two of the most prominent African American architects in the nation. The new project was heavily involved with the community from the beginning. From 1977 to 1987, the MBTA special office for the project chaired over 1,000 community meetings.[8] Integral to these meetings was the bridge that Stull & Lee formed between the community and the governmental actors putting the project in motion. The firm’s presentations and explanations of the project was devoid of the usual jargon that reminded the community of the disastrous projects planned by the government in the past. As expected, each neighborhood along the project had different demands for what ought to be included in the park. For example, the South End wanted underground trains, Roxbury wanted children’s areas, and Jamaica Plain wanted gardens. With the destruction of the elevated Orange Line and the new provision giving grants for mass transit projects, an underground train system was an obvious choice.[9] In the process of fleshing out how the park would flank the underground trains, Stull & Lee found that incorporating a variety of demands into the design created a more trusting relationship between the community and all the project planners. The result of this philosophy is a landscape that changes its operations as it runs through different neighborhoods. In Jamaica Plain, where open space was of a high priority, the corridor expands to 250 ft, its widest point in the entire stretch (Figure 2). Further down the corridor in the South End, buildings begin to densify and less room is allotted for sports facilities and playgrounds. The corridor narrows, converting its appearance from a park and cycling path to an urban promenade.[10] Overall, the $747 million project consists o f a wide variety of amenities throughout the land it occupies, including basketball courts, gardens, bike/pedestrian paths, and playgrounds. Additionally, the subway stations incorporated into the layout of the park provides a seamless threshold between green and transit infrastructure. Exemplary of this transition is Jackson Square Station (Figure 3). The station sits adjacent to the pedestrian and bike paths that run through the entire Southwest Corridor. Additionally, murals are painted on the front columns of the building as well as the side façade. This colorful artwork reflects the character of the community onto the building and is a connection to the local artists that painted them.

The community’s contributions to the form and character of the Southwest Corridor made it a network that connected diverse neighborhoods. Since the park brought greenspaces, playgrounds, and transportation to the doorstep of the adjacent neighborhoods, nearby properties became very desirable. The new pieces of infrastructure gave citizens who worked downtown an opportunity to remove themselves from the urban core while maintaining a commutable distance to it. The downsides of the project are evident in the way the Boston housing market reacted to the project. Since available space in cities is always decreasing, property values will trend upward in almost any given time period. This is what generally results in higher rents and costs of living. In Boston, urban renewal in the form of the Southwest Corridor Project resulted in an uneven distribution in where property values increased the most. In 1990, as the Southwest Corridor was being completed, there were 59 census tracts in the Boston area whose median home values were below the region’s median. These tracts, primarily located in neighborhoods like Roxbury, also saw a 50% increase in median home values from 1990 to 2016 – more than twice the regional change. Rent changes tell a similar story. Real median rents (those adjusted for inflation) increased in 73% of census tracts, with the largest increases taking place in neighborhoods like Jamaica Plain.[11] As discussed before, the majority of residents in these neighborhoods were working class minority families. Not only did the cost of living go up for these families, but their incomes would not keep pace. Census tracts in neighborhoods like Roxbury saw real median household income decline by over 10%. Conversely, places like downtown Boston saw real median household income increase by over 20% from 1990 to 2016.[12] Though the Southwest Corridor Project has no measurable effect on income, what is illustrated is a lack of preparation on the part of the government to create a safety net for low-income residents in the adjacent neighborhoods. If incomes cannot be kept to pace with rising property values and rent, safety nets must be created in the form of public housing and/or rent subsidies. Neither of these measures were taken in a way that would protect residents. Public housing gives those who cannot keep up with rent an alternative living space in the same area. This prevents uncontrolled gentrification, where a neighborhood populates with a higher-income, usually homogeneous racial population. Unfortunately, Roxbury’s population demographics would shift in the years after the completion of the Southwest Corridor. The share of the African American population in Roxbury would fall from 78.9% in 1980 to 53% in 2015. The South End would also see its percentage of African American residents fall by half.

Gentrification does not always have to be a destructive force. When done correctly, gentrification can create heterogeneous racial makeups, stable housing markets, and safer living conditions. As long as subsidies are provided in the form of rent or housing, increases in property values will result in an increase in property-tax - allowing for better, more efficient community services.[13] This gives lower-income residents better living conditions and a better chance to see overall increases in income in the long term. Such was not the outcome with the communities along the Southwest Corridor. The city of Boston ought to have seen the forthcoming hike in property values. If they had, they could have provided public housing and/or rent subsidies to protect those residents who would not be able to keep up with the cost of living. Instead, longtime residents were forced from their homes, as seen in the marked loss in share of minority populations in neighborhoods like Roxbury. Donald Stull and David Lee played the ideal role as a bridge between the government and people. They designed a beautiful park and transit system that revitalized several communities. Had the government done its job to protect its vulnerable populations, perhaps more citizens would be able to enjoy the marvelous greenspaces of the Southwest Corridor.

[1] Andre Torre, Vu Hai Pham, and Arnaud Simon, The ex-ante impact of conflict over infrastructure settings on residential property values: The case of Paris’s suburban zones (London: Sage Publications, 2015), 2405.

[2] Jim Vrabel, A People's History of the New Boston (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 139-140.

[3] Karilyn Crockett, People before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2018),

[4] “Historical Trends in Boston Neighborhoods Since 1950,” Research Division, BPDA, last modified December, 2017, http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/89e8d5ee-e7a0-43a7-ab86-7f49a943eccb.

[5] Vrabel, A People's History, 139-140.

[6] Torre, Hai Pham, and Simon, The ex-ante impact, 2408.

[7] Vrabel, A People's History, 149.

[8] Travis Dagenais, “Remembering pioneering Black architect Donald L. Stull (1937–2020)”, Harvard Graduate School of Design, January 7th, 2021.

[9] Catherine Foster, “Subway With a Park on Top. Boston's Southwest Corridor has train tracks below, green areas and recreation above. URBAN DESIGN: MASS TRANSIT”, The Christian Science Monitor, February 24th, 1989.

[10] Katherine Crewe. "Linear Parks and Urban Neighborhoods: A Study of the Crime Impact of the Boston South-west Corridor." Journal of Urban Design, (2001): 250-254.

[11] Alexander Hermann, David Luberoff, and Daniel Mccue, “Mapping Over Two Decades of Neighborhood Change in the Boston Metropolitan Area”, (Research Brief, Harvard University, 2019), 5-6.

[12] Hermann, Luberoff, and Mccue, “Mapping Over Two Decades of Neighborhood Change in the Boston Metropolitan Area”, 3-4.

[13] “Bring on the Hipsters,” The Economist, February 21, 2015.

References

Crewe, Katherine. 2001. "Linear Parks and Urban Neighborhoods: A Study of the Crime Impact of the Boston South-west Corridor." Journal of Urban Design 245-264.

Crockett, Karilyn. 2018. People Before Highways: Boston Activists, Urban Planners, and a New Movement for City Making. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Dagenais, Travis. 2021. "Remembering pioneering Black architect Donald L. Stull (1937–2020) ." Harvard Graduate School of Design, January 7.

Division, BPDA Research. 2017. Historical Trends in Boston Neighborhoods Since 1950. Research, Boston: Boston Planning & Development Agency.

Foster, Catherine. 1989. "Subway With a Park on Top. Boston's Southwest Corridor has train tracks below, green areas and recreation above. URBAN DESIGN: MASS TRANSIT." The Christian Science Monitor, February 24.

Hermann, Alexander, David Luberoff, and Daniel Mccue. 2019. Mapping Over Two Decades of Neighborhood Change in the Boston Metropolitan Area. Research Brief, Cambridge: Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

The Economist. 2015. "Bring on the Hipsters." February 21.

Torre, Andre, Vu Hai Pham, and Arnaud Simon. 2015. "The ex-ante impact of conflict over infrastructure settings on residential property values: The case of Paris's suburban zones." Urban Studies 2404-2424.

Vrabel, Jim. 2014. A People's History of New Boston. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Figure 1. Central Artery, circa 1969. (Massachusetts Department of Public Works)

Figure 2. Wide, open spaces on the Southwest Corridor, circa 2010. (Southwest Corridor Park Conservancy)