Background:

The American landscape in the latter half of the 20th century was dominated by suburbanization. Emerging from the end of the Second World War, America vaulted itself into a period of growth that would result in the emergence of a robust middle class, a massive demographic shift across the nation, and segregation that would scar our cities for decades to come. As soldiers returned from the war, federal credit programs such as those sponsored by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) provided opportunities for soldiers to purchase homes at a fraction of their cost.[1] The standard model of this type of home is embodied in the Levittown homes. Created by William J. Levitt, these homes were manufactured on assembly lines and featured elements of the suburban home that are now considered stereotypical: White picket fences, gabled roofs, and green lawns (Figure 1). As suburban life and the prospect of owning land became a model for the 20th century American Dream, suburban neighborhoods began to sprawl, defining the landscapes of towns outside major cities. The populace that occupied these new towns left a void in their old urban dwellings located in the inner cities. This void would quickly be filled by African American citizens migrating north during the Second Great Migration.[2] Unfortunately, the middle-class dreams created in the suburbs were primarily available to White citizens. Segregation would exist in both de jure and de facto forms by way of restrictive covenants and the practice of redlining. From the 1930s, the FHA sponsored the inclusion of racialized restrictive covenants in the deeds of homes that it insured. These legal documents denied the sale of the property to Black Americans. This practice would extend into the private sector with the creation of redlining maps: neighborhoods would be color coded to reflect the relative risk of insuring loans to them – with red indicating the highest risk. Unfortunately, these areas were almost always determined by the racial makeup of the neighborhoods. As a result of these designations, Black neighborhoods in cities across the United States would face disinvestment, dilapidation, and disparities in almost every social metric.[3] Though these segregationist policies satisfied the racist urges of White policy makers at the time, the conditions created by these housing policies would haunt the whole of the American populace right through the present moment.

Changing Demographics:

Though the racist, legislative elements of American housing policy have largely been struck down, the legacy of those laws and practices lives on through the segregation patterns seen across American neighborhoods. Throughout the studies examined in this literature review, the terms “census tract”, “neighborhood”, and “community” are used interchangeably, as they refer to the same concept: areas subdivided by particular demographic, statistical, or geographic bounds. By 2010, the percentage of White Americans living in suburbs was 63%, compared to just 40% for Black Americans.[4] Since suburban homes are generally more expensive than inner-city apartments, the disparities between the earnings of different races can account for this present-day segregation. Nationally, 31% of White children born at the lower end of the economic ladder will remain there as adults. For Black children this figure is 48%, meaning that almost half of low-income Black families will see their children remain poor as adults.[5] In an effort to bridge this gap, both federal and state governments sought to implement measures such as mixed-income housing and denser zoning laws to bring together different socioeconomic levels into the same neighborhood.[6] Projects like the “HOPE IV” housing developments provided housing in diverse income areas to those affected by the slum-clearance efforts of the urban renewal movement. These developments showed success: youths that moved from urban public housing to racially and economically diverse neighborhoods showed higher employment rates than those who moved to racially homogenous neighborhoods.[7] Efforts to create racially or economically diverse neighborhoods are not always successful. Zoning laws in American cities commonly strike down proposals for mixed use and affordability. The result of this has been a domination of American housing stock by two premier types of housing: the single-family detached home (SFDH) - as seen across American suburbs - and the mid-rise apartment building - as seen in inner cities.[8] While the type of housing stock has remained constant, the makeup of American society has not: census projections estimate that, by 2060, the American population will be majority minority, with non-Hispanic White citizens making up just 44.3% of the population.[9] With this marked demographic shift, it follows that the landscape of the American family has changed drastically since the post-war nuclear family of the 20th century. Two-parent households are declining and overall family sizes are smaller, leaving no single dominant family form in the US.[10] As these households search for adequate housing for their dynamic needs, they are often faced with the choice between either the SFDH or the mid-rise apartment. Since the purposes of these housing types were defined in the late 20th century, they are archaic in the current, post-nuclear family era.

Existing Friction:

This mismatch between our needs and our housing’s ability to meet them leaves us with the groundwork for a housing crisis. Contemporary studies on the housing market show that, much like the diminishing marginal product of labor related to quantities of workers, saturating the housing market with SFDHs and mid-rise apartment complexes provides diminishing returns after the nth unit is built. This can result in either unoccupied units and/or upward market pressure on other types of housing, whose demand will balloon.[11] The rent and price increases related to this intense competition will give preference to those households with greater financial leverage to out-bid all others. For lower-income households, this may lead to the purchasing homes that are beyond their means by way of a subprime loan. Currently, urban planners and residents alike show hesitancy when confronted with the prospect of increasing the density of their neighborhood with new affordable housing projects. The typical argument is that the mere presence of affordable housing in a neighborhood will decrease property values for existing residents. In the era of White flight, this was a self-realizing cycle as White residents would leave neighborhoods and take their accumulated wealth and investment with them. However, the actual practice of adding affordable housing is more complex: the quality, design, and management of housing is what decides its contribution to neighborhood property values, not merely its existence.[12] Furthermore, it would seem that the loud dissidents of affordability in our neighborhoods, as characterized by the NIMBY (not-in-my-backyard) movement, do not always speak for their neighbors. Surveys conducted to find latent demand for higher density, transit-oriented development (TOD) projects found that though 40% of households showed preferences for TOD neighborhoods, 37% of this group currently lived in car-oriented, SFDHs. Two different implications arise from this mismatch: well-to-do households may pay a premium for TOD housing that better fits their needs, and households seeking affordability would be better off with options that did not force them into a more costly SFDH.[13]

The Benefits of Greater Housing Diversity:

Critics of higher density housing developments too often focus on what could go wrong with greater density at the expense of focusing on what could go right. Though the process of approving and constructing these, and any, types of new housing is long and difficult, studies on successfully implemented projects have illustrated the wealth of benefits brought at all scales of the community. The HOPE VI projects provide a strong case study for examining the small-scale benefits of housing diversity, such as those at the individual and family levels. A study on the benefits of HOPE VI housing on employment prospects examined 257 HOPE VI sites around the country. Using site and census tract data, the study found that housing type diversity was a significant predictor of new job placements. Since these housing projects were also mixed-income, the study discussed the improved strength of social networks created by mingling low-and-high-income residents.[14] A different study from Grand Valley State University examined the connection between housing diversity more generally to various social metrics. The researchers found that their housing diversity score has a strong, negative correlation with unemployment.[15] Moving up to the neighborhood scale, housing diversity can have a tangible effect on rates of foreclosure and default between census tracts. These questions became particularly pertinent following the 2008 financial crisis when low-income citizens fell prey to predatory lending practices such as subprime mortgage loans. Studying these effects, researchers out of the University of Illinois looked at how census-level data in metropolitan study areas (MSAs) around the country compared to their respective housing diversity and zoning diversity scores. The researchers were interested in how housing and zoning diversity impacted both foreclosure and sales rates in each census tract. These rates measure the relative extent of downturn and recovery respectively. They found positive correlation between population growth rate, foreclosure rate, and sales rate. Particularly for cities that prioritize zoning for high-income development, this relationship gives credence to the notion that families must pursue subprime loans to finance homes above their means.[16] Furthermore, the same study found that the housing diversity index (HDI) for each MSA was positive and significant for all models of foreclosure. Additionally, low housing diversity tracts also displayed lower sales rates in the years following economic downturn, suggesting slower economic recovery for homogenous neighborhoods.[17] This finding ought to come as a relief to those that oppose housing diversity due to perceived decreases in property values. It is housing diversity that stabilizes communities in times of economic hardship.

What Does Middle Density Look Like?:

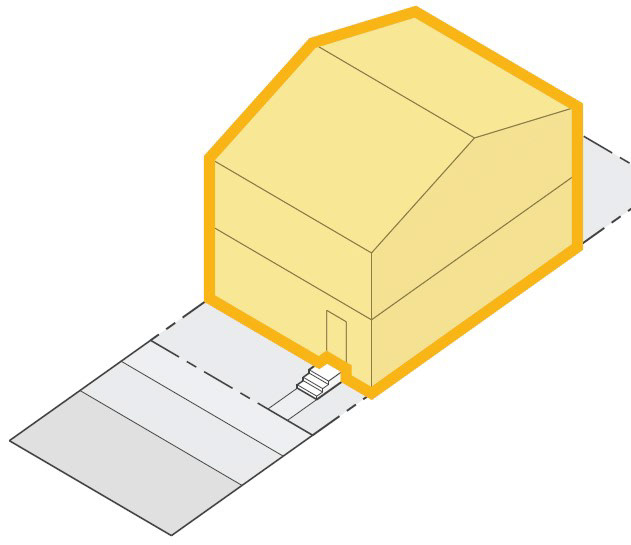

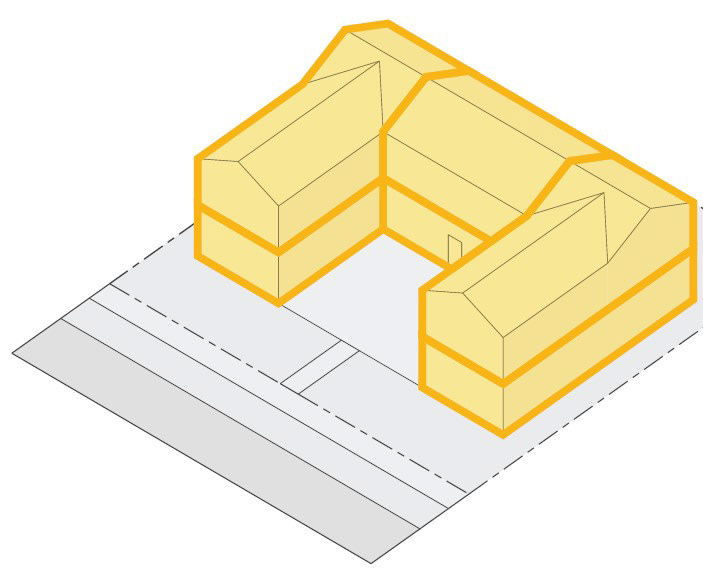

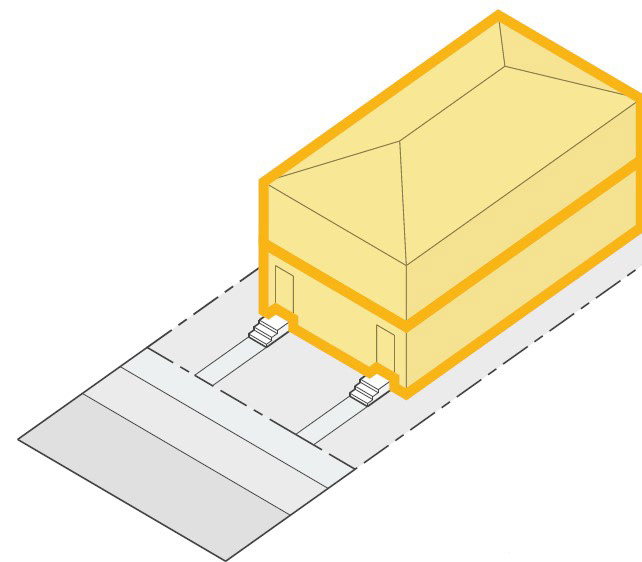

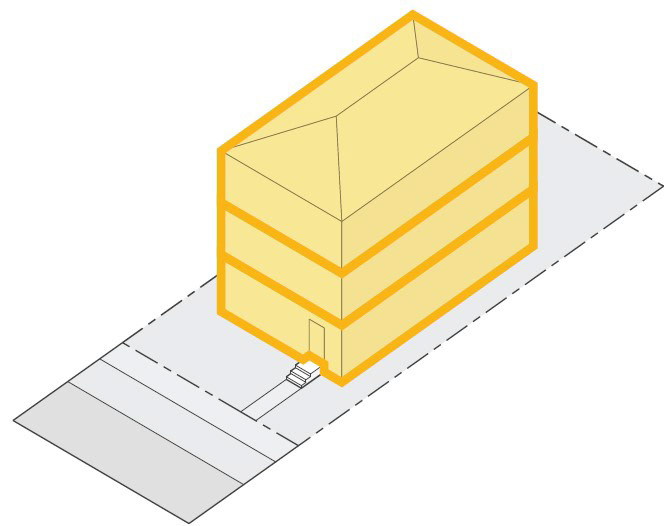

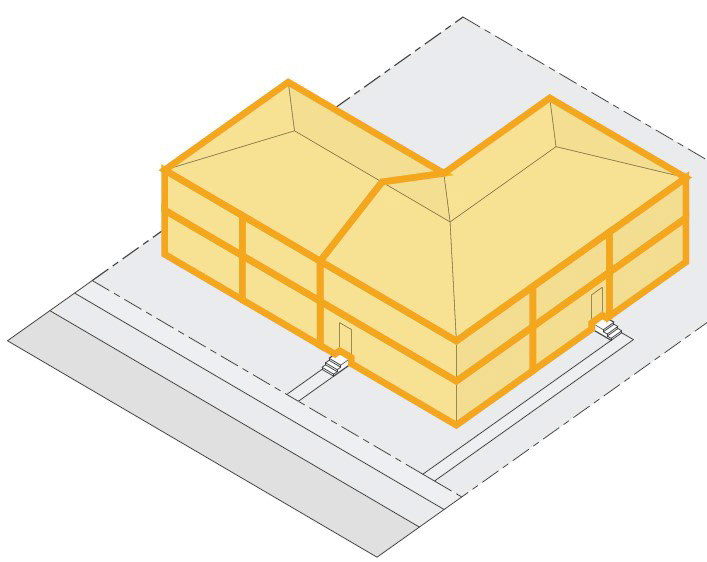

Introducing new housing types to a neighborhood brings more changes than just those that are economic. The details, sizes, and character of these different spaces can physically and demographically change a neighborhood fabric. This is mostly due to the change in density these housing types introduce. In suburban neighborhoods (Figure 2), middle-housing would increase density (Figure 3). With inner-city neighborhoods that are currently higher density (Figure 4), the opposite would be true. In his widely influential book calling for the implementation of missing-middle housing, Daniel Parolek breaks down the characteristics of popular middle-housing types. Parolek explains how these types are meant to be adaptable to the sites that they serve. Furthermore, the various types share a few key traits, despite their aesthetic differences. These traits include a maximum of two-and-a-half to three stories, maximum of nineteen units per building, 55–75-foot maximum width along the street with a 55–65-foot maximum depth, a maximum of one non-street parking space per unit, and shared, public open space.[18] Popular middle-density housing models include, but are not limited to, courtyard buildings (Figure 5), stacked duplexes (Figure 6), stacked triplexes (Figure 7), multiplexes (Figure 8), and townhouses (Figure 9). The limit to the number of units in each of these types allows the individual units to occupy more space in the building, skewing the demand for these types of structures to be made up of families and households larger than just two. Parolek’s examination and description of these housing types is in line with earlier studies on competition between different households on the types of units they rent.[19] The introduction of these units into a neighborhood breaks the current supply-demand dichotomy of SFDH and mid-rise apartment. Now, supply-demand curves exist for each of these units separately, easing competitive pressures on rent prices and overall housing availability.

Problems With Implementation:

Though the push to suburbanize the outsides of our cities while densifying their insides discussed at the beginning of this literature review dominated our 20th century urban planning, the concept of injecting middle-density housing into a neighborhood to right previous wrongs has been revived in recent times. It is important to note that these conversations are not limited to American borders. One case-study involving the implementation of new housing code takes place in Sydney, Australia. The New South Wales (NSW) “Low Rise Housing Diversity Code” came into effect in July of 2020 with the expressed intent of addressing lack of affordability and housing homogeneity in Sydney’s housing market.[20] Much like the US, Sydney’s residents lived in predominantly SFDH housing outside of the city and high-density apartments inside the city. Furthermore, existing residents and urban planners fought against the introduction of affordable housing by stalling project development or stopping it outright. The new Code implemented shortened approval periods for housing that met certain middle-density criteria – guidelines that echo Parolek’s prescriptions for missing middle housing. The Code even spelled out the specific types, such as duplexes, triplexes, and manor houses, that would clear the approval periods the quickest.[21] On paper, this legislation implements the proper approaches to diversifying neighborhoods that have available space and are currently homogeneous. The problem arose with the decision of the NSW Planning Council to leave approvals up to local authorities. This gave the Code no teeth with which to push housing diversity through stubborn municipalities, creating the same situation as before where NIMBY residents and planners are allowed outsized authority. Following the Code’s adoption, various local councils amended their local environmental plans (LEPs) to limit the applicability of new housing types to the local land use policies.[22] It is not difficult to see how a similar situation could play out in the United States, with federal laws being hindered by state or local execution of the laws. In fact, many municipalities in the US already have these limitations in place. It is important for state governments to understand the stabilizing power of housing diversity, as described in previous sections, and unilaterally implement diverse housing and zoning laws.

Conclusions:

Bringing new housing to a neighborhood is a process that inherently changes some, if not most, aspects of that neighborhood’s character. Many refer to this phenomenon as gentrification. For people on all points of the political spectrum, this word is typically read with a negative connotation. In the current, urban American context, gentrification typically involves injecting a community with uninspiring, simplistic apartment buildings that will raise rental prices and force existing residents to move.[23] Missing middle housing can change the stigma around this term. Fundamentally, gentrification is defined as the changing of a neighborhood’s character. This can be a good thing. As examined in the current literature, middle-density developments have the power to stabilize neighborhoods economically and demographically, righting the many wrongs of 20th century American urban planning. With the precise injection of housing diversity and open space, American neighborhoods can promote better relationships between residents and their neighborhoods, and in turn, neighborhoods and their cities.[24]

Footnotes:

[1] Douglas S. Massey & Jonathan Tannen, “Suburbanization and segregation in the United

States: 1970–2010”, Ethnic and Racial Studies (April 2018): 1594.

States: 1970–2010”, Ethnic and Racial Studies (April 2018): 1594.

[2] Massey & Tannen, “Suburbanization”, 1595.

[3] Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law, New York: Liveright,

2017), 42.

2017), 42.

[4] Massey & Tannen, “Suburbanization”, 1599.

[5] Steiner et al., “Equity in Economic Opportunity”, The Polis Center (May 2021): 12.

[6] Seungjong Cho and Miyoung Yoon, “A study on employment of HOPE VI projects: Examining the impact of neighborhood disadvantage, housing type diversity, and supportive services”, Journal of the Housing Education and Research Association (February 2019): 23.

[7] Cho & Yoon, “HOPE VI”, 25.

[8] Chad Frederick, “Economic Sustainability and ‘Missing Middle Housing’: Associations between Housing Stock Diversity and Unemployment in Mid-Size U.S. Cities”, MDPI Sustainability (June 2022): 1.

[9] “Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060”, Population Estimates and Projections, US Census, last revised February 2020, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf.

[10] Pew Research, “Parenting in America: Outlook, worries, aspirations are strongly linked to financial

situation”, Pew Research Center (December 2015): 15.

situation”, Pew Research Center (December 2015): 15.

[11] Frederick, “Economic Sustainability”, 5.

[12] Arnab Chakraborty and Andrew McMillan, “Is Housing Diversity Good for Community

Stability? Evidence from the Housing Crisis”, Journal of Planning Education and Research (September 2018): 151.

[13] Yu Huang, Dawn Parker, and Leia Minaker, “Identifying latent demand for transit-oriented development neighbourhoods: Evidence from a mid-sized urban area in Canada”, Journal of Transport Geography (January 2021): 9.

[14] Cho & Yoon, “HOPE VI”, 34.

[15] Frederick, “Economic Sustainability”, 10.

[16] Chakraborty & McMillan, “Is Housing Diversity”, 157.

[17] Chakraborty & McMillan, “Is Housing Diversity”, 158.

[18] Daniel Parolek, “Missing Middle Housing Types,” in Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today's Housing Crisis, (Albany: Island Press, 2020), 93–94.

[19] Frederick, “Economic Sustainability”, 5-6.

[20] Angelo Korsanos, “The failure of the ‘Housing Diversity Code’ to deliver housing diversity,” Australian Planner (August 2022): 1.

[21] Korsanos, “Failure of the ‘Housing Diversity Code’”, 2.

[22] Korsanos, “Failure of the ‘Housing Diversity Code’”, 3.

[23] The Economist, “Bring on the Hipsters,” The Economist, February, 19th, 2015, https://www.economist.com/united-states/2015/02/19/bring-on-the-hipsters

[24] Antonio Zumelzu & Marie Geraldine Herrmann-Lunecke, “Mental Well-Being and the Influence of Place: Conceptual Approaches for the Built Environment for Planning Healthy and Walkable Cities”, MDPI Sustainability (June 2021): 11.

References:

Chakraborty, Arnab, and Andrew McMillan. 2018. "Is Housing Diversity Good for Community Stability? Evidence from the Housing Crisis." Journal of Planning Education and Research 150-161.

Cho, Seungjong, and Miyoung Yoon. 2019. "A study on employment of HOPE VI projects: Examining the impact of neighborhood disadvantage, housing type diversity, and supportive services." Journal of the Housing Education and Research Association 23-37.

Frederick, Chad. 2022. "Economic Sustainability and ‘Missing Middle Housing’: Associations between Housing Stock Diversity and Unemployment in Mid-Size U.S. Cities." MDPI Sustainability 1-17.

Herrmann-Lunecke, Marie Geraldine, and Antonio Zumelzu. 2021. "MentalWell-Being and the Influence of Place: Conceptual Approaches for the Built Environment for Planning Healthy and Walkable Cities." MDPI Sustainability 1-21.

Huang, Yu, Dawn Parker, and Leia Minaker. 2021. "Identifying latent demand for transit-oriented development neighbourhoods: Evidence from a mid-sized urban area in Canada." Journal of Transport Geography 1-13.

Korsanos, Angelo. 2022. "The failure of the ‘Housing Diversity Code’ to deliver housing diversity." Australian Planner 1-5.

Massey, Douglas S, and Jonathan Tannen. 2018. "Suburbanization and segregation in the United." Ethnic and Racial Studies 1594-1611.

Parolek, Daniel. 2020. "Missing Middle Housing Types." In Missing Middle Housing : Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today's Housing Crisis, by Daniel Parolek, 91-175. Albany: Island Press.

Pew Research Center. 2015. Parenting in America: Outlook, worries, aspirations are strongly linked to financial situation. Demographic Study, Washington D.C.: Pew Research Center.

Rothstein, Richard. 2017. The Color of Law. New York: Liveright.

Steiner, Erik, Matt Nowlin, Jeramy Townsley, Rebecca Nannery, Unai Miguel Andres, and Sharon Kandris. 2021. Equity in Economic Opportunity. Research Report, Indianapolis: The Polis Center.

The Economist. 2015. "Bring on the Hipsters." February 21.

Vespa, Jonathan, Lauren Medina, and David M Armstrong. 2018. Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060. Population Estimate, Washington D.C.: US Census Bureau.

Figure 1: A Standard Levittown Home (Via Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc)

Figure 2: A Typical Set of Suburban Blocks (Via Charles Marohn)

Figure 3: Rowhouses in Boston’s South End (Via Anna C. Jacobson)

Figure 4: New High-Rise Apartments in Manhattan (Via NYTimes)

Figure 5: Courtyard Building (Via Daniel Parolek)

Figure 6: Stacked Duplex (Via Daniel Parolek)

Figure 7: Stacked Triplex (Via Daniel Parolek)

Figure 8: Multiplex Building (Via Daniel Parolek)