Studying economic growth can give snapshots of a particular country, region, or city during a period of time. It provides us with necessary context to begin a more nuanced examination of that region’s performance. The typical yardstick of growth, gross domestic product (GDP), is the value of all final goods and services produced by a country, region, or city in a given period. Between 1870 and 1929, the U.S GDP per person grew at a rate of 1.76% per year.[1] This unprecedented rate of growth was largely thanks to the Second Industrial Revolution, which began in 1850. However, GDP is a broad measure of output that does not tell the full story of growth. This period also had a similar, parallel effect on architectural practice through the usage of new materials and construction processes available to designers and developers. These new materials, along with the parallel expansion of the railroad into the American Midwest, brought economic growth to the expanding regions outside of the East Coast. By examining architectural innovations in tandem with measures such as output, income, and labor, we can paint a more complete picture of growth and its impact on architecture. A prime example of this relationship is seen in Chicago. Situated in the heart of the Midwest, Chicago was a rapidly expanding city that served as a middleman for manufactured goods from the East Coast and primary products from the West.[2] As we will see, the explosive economic growth seen in Chicago greased the engine of architectural innovation in the city. Increases in capital, labor, and investment afforded the exploration of new building typologies and construction technologies that Chicago’s greatest architects would use to define the modern cityscape.

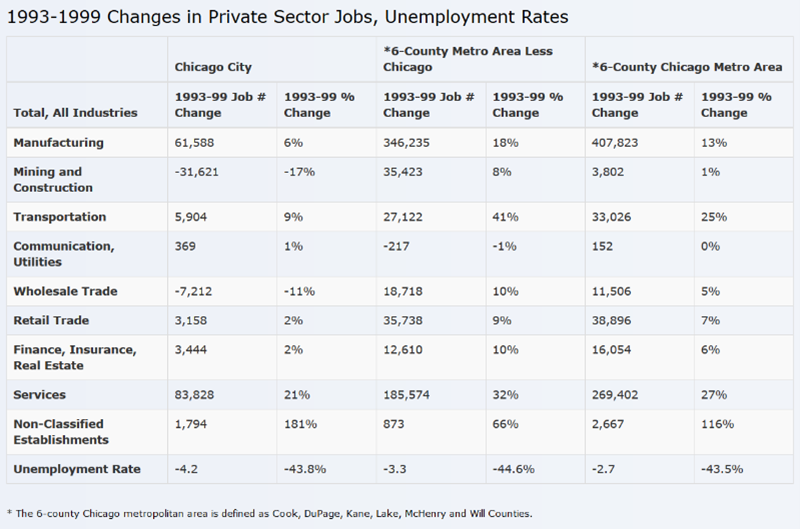

In 1870, the last spike of the Transcontinental Railroad was driven into the Earth. The completion of this railroad allowed for the safe, efficient transportation of people, goods, and resources across the country. The subsequent formation of a national market catalyzed the rapid growth and industrialization in western regions. The Midwest had quickly become attractive for resource-based industries due to the abundance of sites with coal and iron ore. Additionally, the prospect of employment created by the country’s westward expansion gave the region a steady labor supply.[3] Chicago was the driving force behind the Midwest’s growth. As a rapidly growing city, Chicago was the Midwest’s hub for commerce, transportation, and industry. Manufacturing plants and railroads made the region’s resources available to the national market. Between 1860 and 1900, the Midwest’s share of national manufacturing value had increased from 14 to 26 percent.[4] This shift to an industrial economy led to a marked increase in the region’s personal income (Figure 1). As seen in the figure, the East North Central region (encompassing Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio) sees a dramatic increase in personal income starting in the 1860s. Increases in income reflect both the trends of the labor market and the product market. As the demand for labor went up (spurred by the rapid expansion of industry), so too did the average wage for a worker.

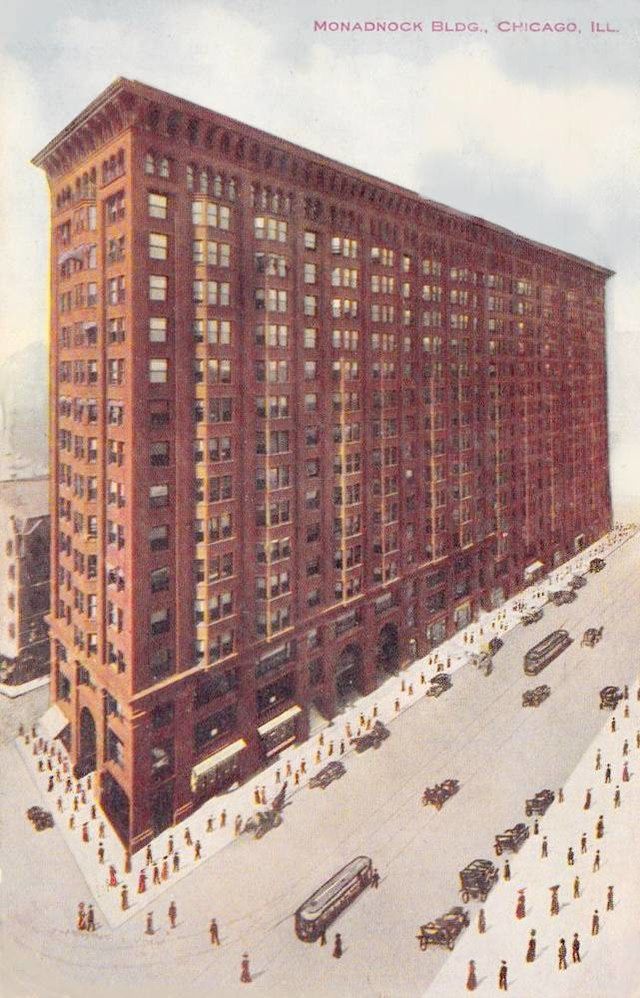

The shift of resources and capital to the Midwest fostered many technological innovations in urban centers like Chicago. As Chicago’s population began to burgeon, so too did the demand for buildings that would accommodate housing and commercial activity.[5] The popularization of steel in the 1890s facilitated the fullfilment of this demand. Vertical construction in Chicago’s urban core relieved the city’s growing horizontal sprawl. Steel, with its greater strength and ductability relative to iron, allowed architects and engineers to construct taller buildings without sacrificing structural integrity.[6] Prior to the usage of steel framing, exterior masonry walls, such as those seen in the Monadnock Building (Figure 2), were the main load bearing component of many structures. Masonry wall systems are labor-intensive, as they require skilled craftspeople to lay their components. Since Chicago does not produce its own brick and mortar, these components must be shipped to the construction site, adding additional transportation costs.[7] Both of these factors reduce the cost efficiency of making tall buildings out of masonry units. Though not the only reason, this cost inefficiency prevented tall masonry buildings from being popularized, leaving the Monadnock as the tallest masonry structure in the world.[8]

The shift away from brick as a primary building component occurred when the next best material became more cost-efficient. The aforementioned growth in manufacturing output was due to a dramatic increase in the Midwest’s manufacturing capacity. As the region’s exports increased, so too did its own demand for manufactured goods. This was reflected in the increase in purchases of manufactured goods by both households and businesses.[9] In fact, the boom in export capacity is reflected in Chicago’s labor markets (Figure 3). By 1880, Chicago’s manufacturing employment was higher than that of any other Midwestern city. As labor markets grew, the cost of manufactured goods decreased. This opened the door for a material like steel to flood construction sites. In contrast to the Monadnock, the Reliance Building utilizes a steel framing system as its primary loadbearing system (Figure 4). This framing system affords the building an expressive, glass-abundant façade. The hierarchy of the building follows a typical Greek order: base, shaft, and capital. The base is comprised of the ground floor, occupied by a lobby and tall storefront windows. The shaft is made up of office levels, each of the same structural and aesthetic modulation. Lastly, the capital makes up the attic of the building, housing its utility elements.[10] The window scheme in this building differs not only in its abundance, but in the sizes of individual windows. The window pattern dominates the façade, leaving only thin articulations of each floor, an innovation impossible without steel framing.[11] Situated just outside of Chicago’s “Loop”, or central business district, the Reliance Building was a major component of Chicago’s prominence as a commercial, industrial, and cultural hub on the national stage. Additionally, the perceived lightness of the building’s façade contributes to a much larger goal of Burnham’s: to project Chicago as the ideal urban landscape, one that had solved the common problems of the contemporary city.[12]

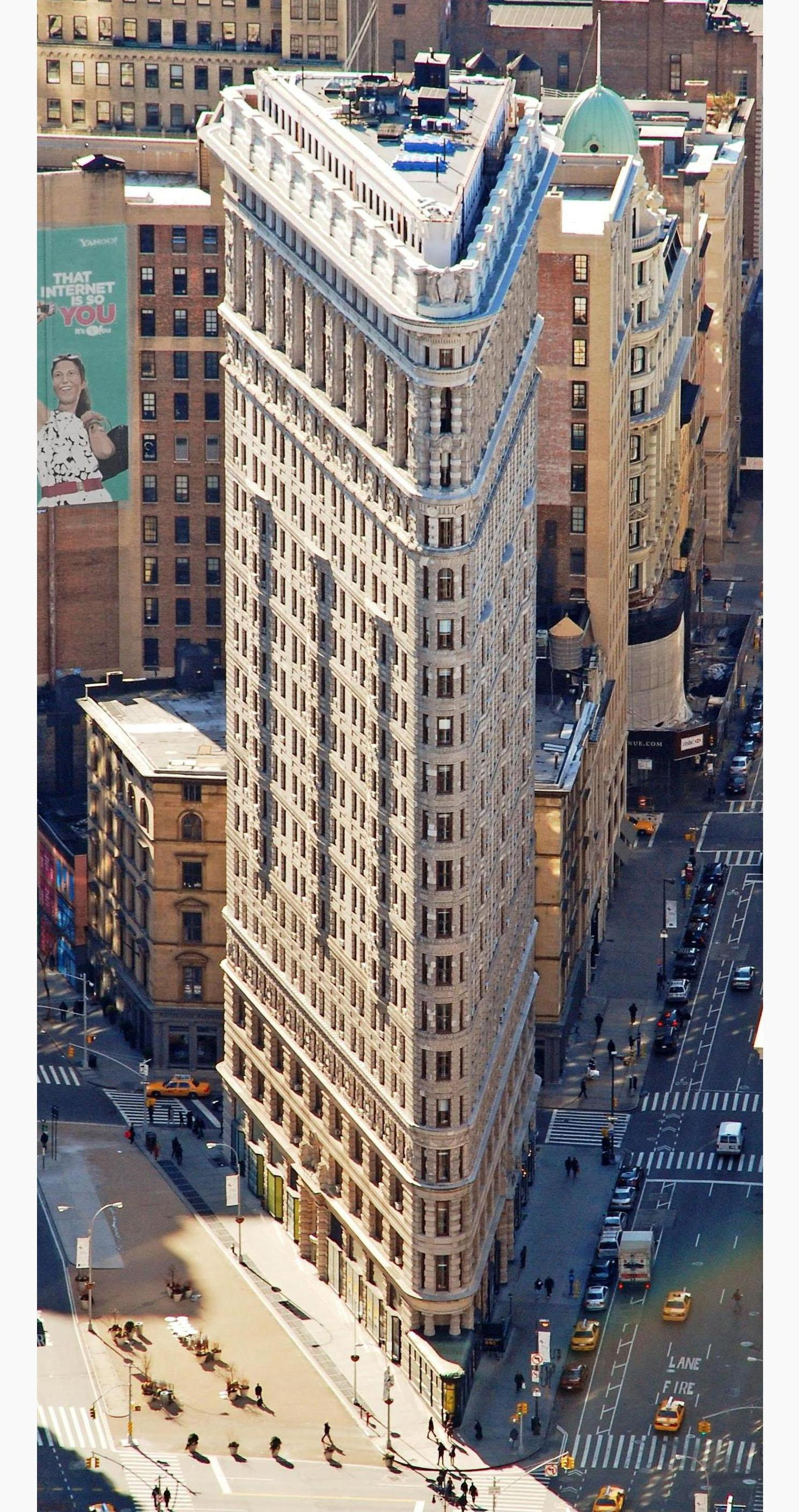

Much of Burnham’s work in transforming Chicago’s cityscape is characterized by the World’s Columbian Exposition, hosted in Chicago in 1893. It is during this fair that the industrial and architectural might of Chicago and the Midwest is put on display. Though Burnham’s uniform monumental neoclassicism took center stage, the influence of Chicago’s skyscrapers was palpable. Burnham’s prominence as an architect led to his designing of buildings outside Chicago. Perhaps one of the most famous of these buildings is New York’s Flatiron Building (Figure 5). Completed in 1902, the Flatiron is a perfect example of the Chicago school’s influence on architecture outside of Chicago. The Flatiron’s usage of repeating floors and Greek order of hierarchy almost mirrors that of the Reliance Building. The structural frame of the Flatiron required some 3680 tons of steel. This steel was transported by rail from the American Bridge Company in the Midwest.[13] From its design to its very structure, Chicago’s influence on this building is unmistakable.

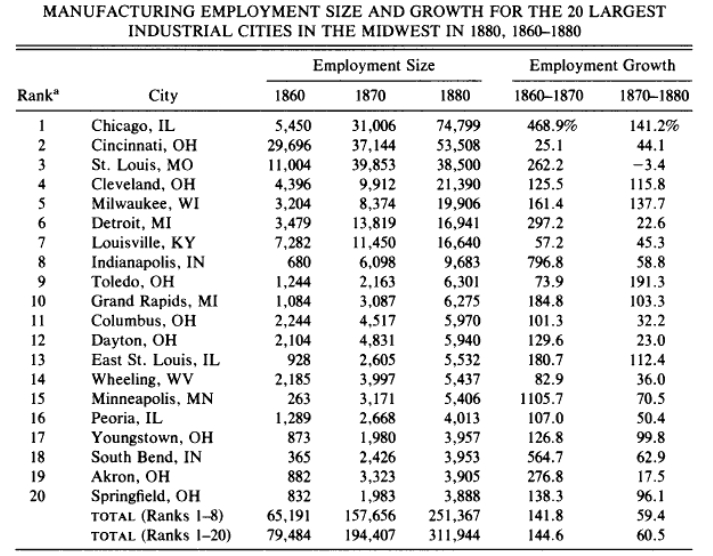

Though architecture and growth followed similar paths in late 19th Century Chicago, economists are ever at odds over how we can predict the trends of future growth. More recent examples worldwide paint a picture that is not as simple as a mere balance between capital and labor. Silicon Valley has seen plentiful investment in the last decade because of the talent that its top firms attract. Despite this, it is unfair to say that this influx of capital and labor has made everyone’s lives better. Soaring property prices have pushed low-income residents out of cities like San Francisco.[14] Innovation has the tendency to follow capital. Architectural innovation is no different. Under free trade, firms in the US found it cheaper to import raw materials, like steel, rather than buy them domestically. This left places like Chicago and the Midwest in economic decline as industry moved elsewhere. Though it is untrue to say that Chicago faded out of relevance, the city has seen a decline in both output and population since the post-war boom (Figure 6).[15] However, plenty of firms still exist here on the cutting edge. As long as these firms continue to push the needle forward, capital and labor are sure to follow: in Chicago and elsewhere.

Footnotes:

[1] Esther Duflo & Abhijit Banerjee, Good Economics for Hard Times (New York: Public Affairs, 2019), 148.

[2] John B. Jentz and Richard Schneirov, Chicago in the Age of Capital: Class, Politics, and Democracy during the Civil War and Reconstruction (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 13.

[3] David R. Meyer, The Journal of Economic History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 922.

[4] David R. Meyer, The Journal of Economic History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 923.

[5] John B. Jentz and Richard Schneirov, Chicago in the Age of Capital: Class, Politics, and Democracy during the Civil War and Reconstruction (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 120.

[6] Thomas Leslie, Built Like Bridges: Iron, Steel, and Rivets in the Nineteenth-century Skyscraper (Berkeley: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians), 237.

[8] Gwendolyn Wright, USA: Modern Architectures in History (London: 2008), 23.

[9] David R. Meyer, The Journal of Economic History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 928.

[10] Louis Sullivan, “The Tall Office Buiding Artistically Considered,”, Lippincott’s Magazine, March 1896, 1-2.

[11] Gwendolyn Wright, USA: Modern Architectures in History (London: 2008), 25.

[12] Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, Chicago 1890: The Skyscraper and the Modern City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 120.

[13] Alexiou, Alice Sparberg, The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City that Arose With It (New York: St. Martin’s Press), 149-150.

[14] Esther Duflo & Abhijit Banerjee, Good Economics for Hard Times (New York: Public Affairs, 2019), 146.

[15] Esther Duflo & Abhijit Banerjee, Good Economics for Hard Times (New York: Public Affairs, 2019), 147.

References:

Alexiou, Alice Sparberg. 2010. The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City that Arose With It. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Banerjee, Abhijit V, and Esther Duflo. 2019. Good Economics for Hard Times. New York: Public Affairs.

Harris, Seymour E. 1961. American Economic History. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jentz, John B, and Richard Schneirov. 2012. Chicago in the Age of Capital: Class, Politics, and Democracy during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Urbana: University of Illinois.

Leslie, Thomas. 2010. "Built Like Bridges: Iron, Steel, and Rivets in the Nineteenth-century Skyscraper." Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 234-261.

Merwood-Salisbury, Joanna. 2009. Chicago 1890 The Skyscraper and the Modern City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meyer, David R. 1989. The Journal of Economic History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sullivan, Louis. 1896. "The Tall Office Buiding Artistically Considered." Lippincott's MAgazine 1-6.

"Top Brick Suppliers and Manufacturers in the USA", Top Suppliers, ThomasNet, accessed December 8, 2020, https://www.thomasnet.com/articles/top-suppliers/top-brick-suppliers-and-manufacturers-in-the-usa/.

Wright, Gwendolyn. 2008. USA: Modern Architectures in History. London: Reaktion Books.

Figure 1: Personal income per capita as a percentage of the US average (1840-1950)

Figure 2: The Monadnock Building (1891) by Burnham and Root

Figure 3: Ranking manufacturing employment size and growth in the 20 largest cities in the Midwest (1880)

Figure 4: Steel frame of the Reliance Building (left) and its finished form (right)

Figure 5: The Flatiron Building in New York City by Daniel Burnham and Fredrick Dinkelberg