Throughout the 20th century, one word could have been used to describe politics in South Africa: apartheid. The apartheid was a racial segregation system in South Africa lasting from 1948 to 1991. It was implemented by the National Party (NP) in South Africa under Daniel Francois Malan and was meant to develop the country’s racial groups separately and keep the minority white South Africans in power – through the justification that they were the superior race. Though apartheid came to the forefront during this time, it is important to note that racial inequalities existed long before the apartheid. These inequalities were merely legalized under the National Party. What came with the apartheid was a both a social and physical barrier between whites and nonwhites (nonwhites included “Blacks”, “Asians”, and “Coloreds” as defined by the NP – all kept separately). Laws put in place by the NP essentially prohibited all contact between members of different races. The separation of different races’ access to public amenities became known as petty apartheid. The other side of apartheid was grand apartheid, or the dictation of opportunities by race. One of the most pronounced effects of petty apartheid was its effect on South African education. Since schools were segregated on the grounds of race, white and nonwhite South Africans lived through different, unequal educational experiences. These social conditions created by the apartheid affect the past, present and future of all South Africa.[1] The medium through which such inequities were created was architecture. The architects of the apartheid era racialized the design and planning of schools to reflect the white presence at the top of the social ladder and the black presence at its bottom. The design philosophy during this time did not follow one artistic movement but rather the movements associated with one continent. As will be shown, architects deliberately made use of European architectural movements such as neoclassicism and modernism in designing for the white State while using oppressive architectural elements for the black population. Such decisions reflect the white superiority that the white South African state wished to impose over the country.

Traditionally, housing dominates the architectural discourse of major cities. Though the effect of housing architecture in the city cannot be understated, housing can only tell us so many stories of societal interaction. Educational infrastructure sometimes plays a much larger role in gauging the development of an area as compared to housing.[2] Education rates are a common statistic used in measuring the development of a country or area. Education can paint a picture of the availability of infrastructure and opportunity in an area.[3] The piece of educational infrastructure that can give it meaning is its architecture. As with any other type of structure, the architecture of a school building can reflect the ideologies of those that commissioned it as well as the ideologies that are taught within it. In South Africa, the NP created racial boundaries around education that were reflected in architecture as well as legislation. In 1952, the Bantu Education Act enforced the racial segregation of South African schools. What came with this was a government overhaul of public education in which black (and other nonwhite) students were given a minimal education such that they would not achieve job positions above those of the servant class.[4] The designs of schools for black students reflected this ideology. The plans for these schools were created by the national government through its National Building Research Institute (CSIR). Because of this, no deliberate usage of architectural style was made. These buildings were typically made of bricks and utilized steel-grilled windows (Figure 1). The reduced nature of this exterior was echoed in the interior layout. The space inside schools was kept to the bare minimum: no allocations were made for libraries, vocational facilities, or recreational activities. Additionally, barbed wire fences often surrounded the land on which the schools were situated (Figure 2).[5] The conditions of these schools remind one of a prison. It is with great intention that the small spaces and bare-minimum materials are used. They are meant to remind black students of their alleged place in South Africa’s society. They are meant to represent the social, and economic “prison” that they are kept in daily as well as the real prison they will end up in if they dare to reject this. The latter manifested in violent, brutal ways. The 1976 Soweto Riots were centered around schools such as the Nadeli High School.[6] These riots started as a result of Afrikaans being declared as the new language through which education would operate. Though this was merely the last straw in a series of events, implementing this language change trumped the native languages of students in these schools and added another layer of oppression upon them. On June 16th, 1976, students planned to march out of their schools in protest. The march evolved into riots due to a brutal showing of police force and as a result, many schools were burned down.[7] Architecture’s role in creating situations like these can be described two ways: first, the initial usage of architectural elements to oppress the student population and keep them at the bottom of the social ladder creates a tangible sense of inferiority among them. The second role of architecture manifests as a result of the first: students are inclined to dismantle the oppressive establishment within which they are forced to conform to the wishes of the oppressing class.

Similarly, schools dedicated to white students also reflected their respective position in society. Their position at the top of the social ladder provided them with access to top-tier South African schooling. A stark contrast with black schools is revealed when examining the stylistic elements of white schools. Since white South Africans were being prepared for the higher-tier jobs in the South African workplace, their schools reflected that in both curricula and aesthetic design. Examples of this arose before apartheid was even implemented. For as long as colonists lived in South Africa, they found ways to distinguish and declare their self-proclaimed superiority over the native population. The Pretoria Boys High School is a shining example of this. Built in 1908 and designed by the Public Works Department chief architect, Piercy Eagle, the Pretoria Boys High School’s main building is laid out symmetrically and uses such elements as arches, pediments, columns, and domes that draw upon Greco-Roman architectural principles.[8] The main building’s façade consists of a central dome that sits above the main entrance. Symmetrically flanking the central space of this building on either side are rows of windows with pediments above them. The upper row of windows has a rounded gable whereas the bottom row has a triangular gable. Resting atop the ends of these flanks are domes that cover an area entered through a set of arches (Figure 3). The heave usage of Greco-Roman elements associates the white students and faculty within the school with a European empire thousands of miles away rather than the local, indigenous context – a move to further declare the difference between the white and native populations.[9] Utilizing these elements gives one’s whiteness the power and authority in this building. This serves as a direct opposite to the state design of black schools where one’s nativity was used to instill inferiority. Symbolism used in the Pretoria Boys High School spoke volumes of the colonists’ views of themselves – views that would be legalized under apartheid.

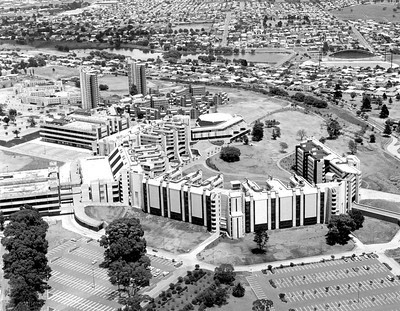

In the mid-20th century under the National Party, new ways were found to instill a white superiority complex within schools. This time, it was manifested in the form of the rapidly popularizing modernist movement. Around the world, modernism was being used to bring legitimacy to new, decolonized powers.[10] South African architects like Rex Martienssen and the “Transvaal Group” were heavily influenced by modernism and the teachings of Le Corbusier. These architects utilized in modernism in a new, South African context. This saw modernism mixed with Eurocentrism. What this meant was that, much like the usage of neoclassic elements in earlier buildings, modernism was being used to link the South African state – specifically its white state – with Europe rather than indigenous state of South Africa.[11] Additionally, modernism was used in tandem with architectural monumentality. Monumentality refers to large built structures that are typically made from stone or similar materials. Totalitarian regimes such as Mussolini’s Italy have utilized monumentality to declare their rule over the land and the powers that previously existed.[12] The Rand Afrikaans University (RAU) in Johannesburg serves as a crucial example of both modernism and the architectural monumentality. Founded in 1967 and designed by Willie Meyer, a student of Louis Khan, the Rand Afrikaans University was originally founded as an Afrikaans language university. As such, the university was initially open exclusively for white South Africans. The building’s design consists of “blocks”, buildings for each department, that are arranged in a circle around an amphitheater (Figure 4). The blocks are made of concrete and are unadorned. The connectedness and concentricity of the blocks gives a high sense of association between the individual blocks.[13] Furthermore, the orientation of the building as an encirclement resembles a laager. Laagers were the circling of wagons by the colonizing Afrikaners in order to shield the inside common area from attack. This image is directly associated to the initial colonization of South Africa. Designing a white South African university in this manner reinforces the white State’s authority over the land.[14] The images used, and produced, by this design diminish the native South African’s role in the land to insignificance. Though this school uses different design elements, it accomplishes the same oppressive goal as a school like the Pretoria Boys High School.

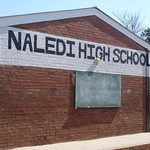

What has been demonstrated is that, regarding education, the National Party made clear the intentions of the apartheid through architecture. The usage of European styles such as neoclassicism and modernism in white South African schools reflect the distinction being made between white South African colonial roots and indigenous South Africans. Additionally, the styles used in educational builds for whites serves as a stark contrast to the design of black South African schools. The resemblance of these schools to jails reflect the message of inferior from the South African government to these communities. This message can be seen in the designs themselves as well as the movements that have emerged from those designs. The tangible effects of this architecture can be seen when looking at statistics concerning the quality of education in South Africa. The 1980 South African census shows that in 1982, the South African government spent the equivalent of ~$65.24 USD on education for each white child and ~$7.87 USD for each black child. Furthermore, while a third of white teachers had a university degree, only 2.3% of black teachers had a degree and 82% had not reached Standard 10 matriculation.[15] These statistics are a direct result of the inequities presented through educational architecture. Worse still, the effects linger into the present day. As of 2000, 10% of former exclusively black schools graduated fewer than 20% of their students and only 7% graduated 80-100% of their students. On the other hand, just 2% of formerly white schools graduated 60-79% of their students while 98% graduated 80-100% of their students.[16] Were it not for the educational architecture that symbolized the State-mandated inferiority of the native population, black South Africans may not kept at the bottom of the social ladder for so long. The “separate but equal development” argument by the National Party in instating apartheid is decisively proved wrong when examining the architectural projects undertaken with respect to the black and white populations. With architecture’s strong role in shaping the course of education throughout recent South African history, one must consider how the South African state can now remediate educational inequalities through the same forces of architecture.

Footnotes:

[1] Elizabeth S. Landis, South African Apartheid Legislation (New Haven, Conn.: Yale Law Journal, 1962), 1-10.

[2] Lesley Naa Norle Lokko, White Papers Black Marks: Architecture, Race, and Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 46.

[3] Pedro Uetela, Higher education and development in Africa (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

[4] Lokko, White Papers Black Marks, 55.

[5] Lokko, White Papers Black Marks, 56.

[6] Lokko, White Papers Black Marks, 57.

[7] Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, "I Saw a Nightmare ": Doing Violence to Memory: the Soweto Uprising (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

[8] Online, South African History. 2011. (South African History Online. July 14.) https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/pretoria-boys-high-school.

[9] Iain Boyd Whyte, National Socialism and Modernism (Stuttgart: Oktagon, 1995), 264-267.

[10] Lawrence Vale, Architecture, Power, and National Identity (London: Routledge, 2014), 121-123.

[11] Daniel Herwitz, Modernism at the margins (Rotterdam: NAi, 1998), 411.

[12] Tim Benton, Rome Reclaims Its Empire (Stuttgart: Oktagon, 1995), 120-122).

[13] Herwitz, Modernism at the margins, 416.

[14] Herwitz, Modernism at the margins, 417.

[15] Alistair Boddy-Evans, School Enrollment in Apartheid Era South Africa (ThoughtCo).

[16] Eric Smalley, Fighting for Equality in Education: Student Activism in Post-apartheid South Africa (New York: Columbia University, 2014).

References:

Benton, Tim. 1995. "Rome Reclaims Its Empire." In Art and Power: Europe under the dictators 1930-45, by Dawn Ades, Tim Benton, David Elliott and Iain Boyd Whyte, 120-122. Stuttgart: Oktagon.

Boddy-Evans, Alistair. 2020. School Enrollment in Apartheid Era South Africa. ThoughtCo. April 3. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.thoughtco.com/school-enrollment-in-apartheid-south-africa-43437.

Herwitz, Daniel. 1998. "Modernism at the margins." In Architecture, apartheid and after, by Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavic, 421. Rotterdam: NAi.

Landis, Elizabeth S. 1962. South African Apartheid Legislation. New Haven, Conn: Yale Law Journal.

Lokko, Lesley Naa Norle. 2000. White Papers Black Marks: Architecture, Race, and Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Online, South African History. 2011. South African History Online. July 14. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/pretoria-boys-high-school.

Pohlandt-McCormick, Helena. 2010. "I Saw a Nightmare ": Doing Violence to Memory : the Soweto Uprising. New York: Columbia University Press. https://hdl-handle-net.ezproxy.neu.edu/2027/heb.99016.

Smalley, Eric. 2014. Fighting for Equality in Education: Student Activism in Post-apartheid South Africa. Case Study, New York: Case Consortium at Columbia University.

Uetela, Pedro. 2017. Higher education and development in Africa. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Vale, Lawrence J. 2014. Architecture, Power, and National Identity. London: Routledge.

Whyte, Iain Boyd. 1995. "National Socialism and Modernism." In Art and Power: Europe under the dictators 1930-45, by Dawn Ades, Tim Benton, David Elliot and Iain Boyd Whyte, 264-267. Stuttgart: Oktagon.

Figure 1: The bare, brick facade of Nadeli High School (Ismail Farouk via Flickr)

Figure 2: Students pose in front of a barbed wire fence outside Moletsane High School (Ismail Farouk via Flickr)

Figure 3: The facade of the Pretoria Boys High School Main Building (African News Agency)